Operation: Cooperation

Last year, I signed up for a program at our local Intergroup office that sends AAs to speak to pediatricians. It works like this:

About once a month, there’s an email blast from the coordinator, requesting participants for a specific day and time. It’s first come, first serve. About 10 AAs arrive at the appointed hour. We’re shown into a conference room, where the doctors are already seated. We don’t give a lecture. Instead, we put on a meeting. The idea is to give the doctors a sense of the AA program, hopefully making them more comfortable to

talk about AA with their patients.

Our “meeting” has a chair who reads a short history of the program. Then we open the meeting with the Serenity Prayer and Preamble. There’s a speaker, who tells his or her story for 20 minutes. Then we all share. I think we’re a bit long-winded and preachy. As usual, I fret about something that doesn’t appear to bother anyone else. The doctors always seem so “present.”

This is not the first time that I have been involved in putting on a meeting for doctors. In the 1980s, I traveled with a group of sober alcoholics to the Soviet Union. We came with copies of the Big Book that had recently been translated into Russian.

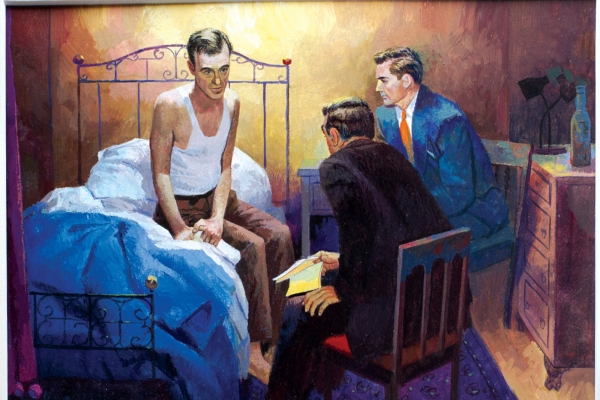

One stop on our itinerary took us to an association of Soviet doctors. My memory conjures an audience numbering in the hundreds, so I assume it was more like 25 to 50. I remember pulling chairs into a circle in the center of a hall with the doctors seated all around us. I remember the mood being oddly quiet and solemn for an AA meeting. No laughter. No buzz of conversation. How could this ever show these doctors what AA is about?

The meeting began. One of us read the Preamble: “Alcoholics Anonymous is a fellowship of men and women ...” (Pause for the translator to catch up: “AHOHV1MHble AnKoronVlKVl 3TO cOAPYlKecTBo MYlKYVlH Vl lKeHlJ.lVlH ...”) The next few minutes amazed me. The audience of doctors seemed to recede from my mind, indeed from the room. (The pause for translation seemed to blend into the rhythm of the meeting.) So it is now with the pediatricians. They seem to disappear from my mind within minutes. I could be sitting in my home group—the power of an AA meeting.

After our sharing, the doctors get to ask questions. I remember one saying that she couldn’t believe how honest we were about our lives. She said that she felt emotional and overwhelmed. We’d literally made her jaw drop. I sense a tremendous weight on the shoulders of these doctors. They wonder what to say to a child who is abusing alcohol. Even with good intentions, they worry about “bungling” the moment and turning the patient off AA altogether.

We close the meeting with the Serenity Prayer, forming a circle and holding hands. We nudge the doctors to join us. It’s a cringe-worthy moment, but they seem to like it.

The only aspect to this service that bothers me is my age. I got sober in my late 20s. I was born in 1957, the tail end of the boomer generation. I grew up in a society very different from today’s. Sometimes I’m not sure what the younger AA members are talking about. So I asked one of my sponsees to join me in this; he’s half my age. I wanted his take. We started doing this commitment together. I asked him to write about his experiences, which you can read below:

Sponsee

When my sponsor suggested that I try a new service commitment outside my circle of meetings, my instinct was to say no, but I said yes. I have attended the doctors’ meeting twice so far. Moment-to-moment, I have not felt the same sense of ease and belonging that settles into me when I am in my regular groups. Yet the experience as a whole has felt, for a lack of a better term, spiritually nutritious. For me, there has been something very special about presenting an AA meeting to outsiders, particularly to doctors who might be able to put what they learned to good use.

Before this, I never thought I had anything of value to share with the medical community. Doctors had never been a part of my story. You hear some alcoholics talk about how a doctor played a crucial role in getting them to AA. Not me. I learned about AA in the isolation of my room—by reading an autobiography of a recovering alcoholic. Then, when I yet again failed to keep my vow of abstinence, I made my own way to the rooms. But somehow sitting in a circle of alcoholics and pediatricians, I remembered times in my using days when my alcoholism did risk coming out of the darkness and showing itself before members of the helping professions. There were multiple sessions of talking to my therapist about getting drunk by myself and feeling shame at what I ended up doing. There was the psychiatrist who I told I thought I might be drinking too much. “They say it’s one day at a time,” she offered. She chuckled when she said that, as if apologizing for speaking such a cliché. Then there was the time I confessed to another psychiatrist that I had gone through a month’s supply of a certain drug for ADHD in less than two weeks. He decided to “monitor” me more closely for the next six months. Doctors did play a role in my story. How well they fulfilled it, however, is another matter.

Of course, I did not offer this last opinion to the pediatricians. I simply spoke of those experiences and hoped that in thinking about them, they might come up with better ways of answering a patient who expresses the same concerns that I’d expressed. I suspect my old doctors glossed over the issue because they felt uncomfortable telling me that I might have a problem. In the two times I participated in this service commitment, I had the sense that in seeing us share our stories so honestly—and with no trace of shame—the doctors were getting more and more comfortable with the subject themselves. They started laughing at all the “right” places, losing some of their professional decorum in the process. It made for quite an amusing scene: a bunch of straightlaced, baby-faced overachievers in crisp white coats taking notes from a group of messed up alcoholics.

At the end of the meeting, the doctors got to ask more questions. Sure enough, many of them wanted to know how to talk to patients about their “problem.” What do they say to get them to try AA? Here’s what I said:

I don’t think it matters so much what you say. Say something! If your patient is ready, he or she will hear you. If they’re not ready, a burning bush in your waiting room couldn’t get through. But what do I know? Maybe there are some pithy words doctors could say. Or maybe there are certain comments that they definitely should not say. So if you can think of anything, you may consider signing up for the next meeting.